-

Who are you?

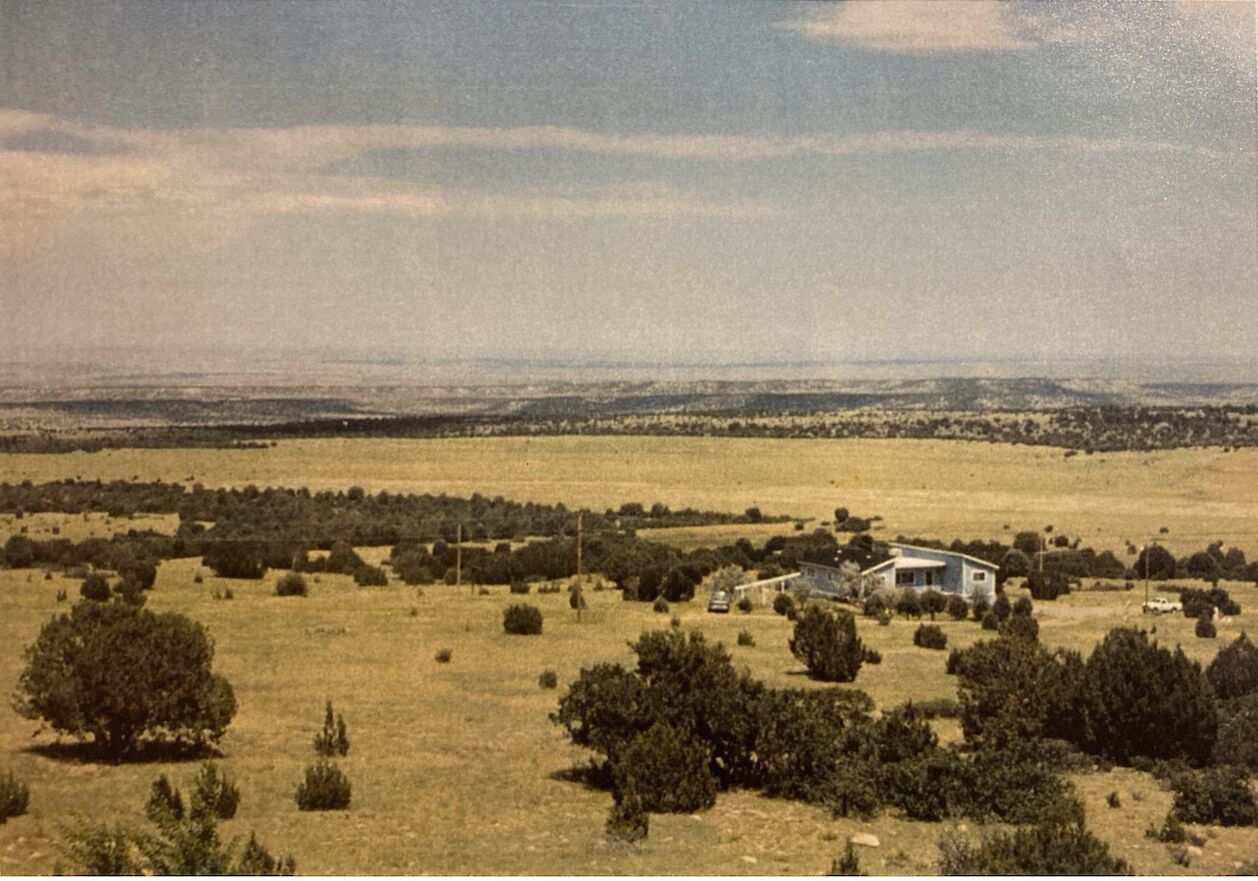

I’m a writer and linguist. I’m originally American and moved from New England to the Netherlands with my family in 2019. We maintain roots in Maine and Texas—lobster barbecue, anyone? Here’s a picture of my childhood home in Colorado.

For about twenty years, my work appeared in the key of journalism, and while I continue to write creative nonfiction, my work is shifting and becoming more academic. From 2008-2013 I was a senior researcher at the FrameWorks Institute. To enable my nonfiction writing, I’ve worked as an editor and grants consultant for over a decade.